I was going to title this post: "Shakespeare Should Never be Taught as Literature." Then I thought some people wouldn't read it thinking it might only be about Shakespeare. Then I thought I'd be sneaky and call it "Never Read a Play Again!" in hopes that high school and college students would read it trying to get out of yet another assignment where they would have to analyze a boring drama by some dead guy who always wore a suit and tie.

Then a miracle occurred.

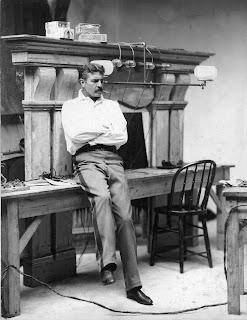

My wife found the following excerpt in a old theatre program. So instead of coming up with thoughts of my own this week, I'm just going to cheat and let you read what the legendary William Gillette had to say about reading plays. It's from his book, The Illusion of the First Time in Acting (New York, 1915, printed for the Dramatic Museum of Columbia University). You can get the ebook on Google Books for free. It's an excellent read for any student of acting, actual actor or theatre historian. So...read on:

"Incredible as it may seem there are people in existence who imagine that they can read a Play. It would not surprise me a great deal to hear that there are some present with us this very morning who are in this pitiable condition. Let me relieve it without delay. The feat is impossible. No one on earth can read a Play. You may read the Directions for a Play and from these Directions imagine as best you can what the Play would be like; but you could no more read the Play than you could read a Fire or an Automobile Accident or a Base-Ball Game. The Play -- if it is Drama -- does not even exist until it appears in the form of Simulated Life."

I have always railed against the teaching of Shakespeare (all plays, actually) in an English class. It is ultimately pointless. Plays are not meant to be read as literature, they are meant to be performed and seen by an audience at that moment. Each performance has the potential to be different from the night before. For the audience, and the actors, a play in performance is visceral. They are meant to be experienced then dissected. Didacticism must follow that intimacy of sitting in the dark.

Imagine trying to teach a class in cinema without watching some movies? A cooking class without food? Can't be done. Same with plays.

Wayne Watkins muses on actors and acting, the arts and artists, and occasionally other stuff.

Monday, February 27, 2012

Monday, February 13, 2012

War Horse. See It.

Movies are manipulative. They are intended to be. That's why we go to them. We accept the fact that a good filmmaker, and even occasionally a bad one, will help us escape into our imaginations for a couple hours. We'll get to go to Pandora and have an adventure with sexy blue aliens, we'll fall in love with Sandra Bullock or Ewan MacGregor, we'll rob a casino with George Clooney, we'll even team up with Samuel L. Jackson and try to retrieve a suitcase stolen from our mob boss. We go to the movies to be swept away. Don't we?

My wife and I went to see War Horse this weekend. This film is based both on a 1982 children's book by Michael Morpurgo and a 2007 stage adaptation of the book (originally mounted at the Royal National theatre in London and now on tour in the U.S.). The movie was directed by Steven Spielberg, music by John Williams, produced by Dreamworks & Disney, blah, blah, blah. You probably know all this is you follow movies at all.

We left the theatre in a shambles. In fact, everyone in the theatre was a wreck. It is a beautiful, old-fashioned, sentimental story. A fabulous story that, yes, manipulates you -- at times to tears. If there is one thing Spielberg knows, it's timing. He has a masterful way of letting you breath in a movie between emotional high points. He knows when to soften a powerful scene with a bit of humor and how to make the character of a horse move you to tears and cheers and gasps.

But as we were walking out of our little neighborhood cineplex, we overheard another couple ask, "Why hasn't this movie done better? Everyone would love this picture." Why, indeed? When we got home, I flung open the iPad and Liz sat at the computer. We both started looking up reviews to find out what the problem was. Very quickly, we found the answer. Thanks to Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic and a few other movie buff sites we frequent, we saw that this film was favorably reviewed by only 75% of people, we'll call them critics, who were writing about it. A full 25% did not like the film or found big flaws in it. How is that? How could this old-fashioned, sentimental beauty of a movie not score higher by everyone who loves movies?

Then it hit us. Like a ton of bricks. It's old-fashioned and sentimental. More John Ford than Christopher Nolan. The "user" reviews were occasionally shocking in their assessment of this movie. Boring, bland, awful, tedious, saccharine, poorly acted, trite, laughably bad. Wow. Granted, we don't know who most of these online "critics" are. No one uses their real name on the internet. But they certainly didn't see the same movie I saw.

Of course, art is subjective. I get it. Some things just may not be your cup of tea. But reading these 25% reviews, I found myself getting rather sad. My fear that we humans (at least a fourth of us, anyway) are denying ourselves the very things that make us human. The ability to empathize, to feel, to imagine. To view art, or life, openly and without filters. Letting it smack us right in the face and permitting our reaction to surprise us then taking it all in and allowing it to wash over us. Certainly, there are some of us who feel the need to cower in our shell and deny our feelings. Some who won't cut loose and risk the chance of their emotions rendering them silly or uncool. Some who don't rage or scream or recoil in fear or sob uncontrollably in the dark. Some of us are above that. Too cool, too considerate, too cynical of any thing that might smack of sentiment.

War Horse began life as a children's book. A successful one. So, I only can assume that kid's get it. But where does that innocence go? When do we pound out of our children the very thing that makes them, and us, human. Do we actively deny ourselves the ability to experience catharsis or are we programmed by others to stop it up. Sentimentality is not a bad thing. If you haven't already, go see War Horse. It's not a "war" movie. It's a story about a boy and his horse and how that horse touches others during a frightening time. I suggest you do with this movie what I advise all my acting students do with art in general: Don't judge too quickly. Let it wash over you in the dark. Allow it to manipulate you. That's why we go to the movies.

My wife and I went to see War Horse this weekend. This film is based both on a 1982 children's book by Michael Morpurgo and a 2007 stage adaptation of the book (originally mounted at the Royal National theatre in London and now on tour in the U.S.). The movie was directed by Steven Spielberg, music by John Williams, produced by Dreamworks & Disney, blah, blah, blah. You probably know all this is you follow movies at all.

We left the theatre in a shambles. In fact, everyone in the theatre was a wreck. It is a beautiful, old-fashioned, sentimental story. A fabulous story that, yes, manipulates you -- at times to tears. If there is one thing Spielberg knows, it's timing. He has a masterful way of letting you breath in a movie between emotional high points. He knows when to soften a powerful scene with a bit of humor and how to make the character of a horse move you to tears and cheers and gasps.

But as we were walking out of our little neighborhood cineplex, we overheard another couple ask, "Why hasn't this movie done better? Everyone would love this picture." Why, indeed? When we got home, I flung open the iPad and Liz sat at the computer. We both started looking up reviews to find out what the problem was. Very quickly, we found the answer. Thanks to Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic and a few other movie buff sites we frequent, we saw that this film was favorably reviewed by only 75% of people, we'll call them critics, who were writing about it. A full 25% did not like the film or found big flaws in it. How is that? How could this old-fashioned, sentimental beauty of a movie not score higher by everyone who loves movies?

Then it hit us. Like a ton of bricks. It's old-fashioned and sentimental. More John Ford than Christopher Nolan. The "user" reviews were occasionally shocking in their assessment of this movie. Boring, bland, awful, tedious, saccharine, poorly acted, trite, laughably bad. Wow. Granted, we don't know who most of these online "critics" are. No one uses their real name on the internet. But they certainly didn't see the same movie I saw.

Of course, art is subjective. I get it. Some things just may not be your cup of tea. But reading these 25% reviews, I found myself getting rather sad. My fear that we humans (at least a fourth of us, anyway) are denying ourselves the very things that make us human. The ability to empathize, to feel, to imagine. To view art, or life, openly and without filters. Letting it smack us right in the face and permitting our reaction to surprise us then taking it all in and allowing it to wash over us. Certainly, there are some of us who feel the need to cower in our shell and deny our feelings. Some who won't cut loose and risk the chance of their emotions rendering them silly or uncool. Some who don't rage or scream or recoil in fear or sob uncontrollably in the dark. Some of us are above that. Too cool, too considerate, too cynical of any thing that might smack of sentiment.

War Horse began life as a children's book. A successful one. So, I only can assume that kid's get it. But where does that innocence go? When do we pound out of our children the very thing that makes them, and us, human. Do we actively deny ourselves the ability to experience catharsis or are we programmed by others to stop it up. Sentimentality is not a bad thing. If you haven't already, go see War Horse. It's not a "war" movie. It's a story about a boy and his horse and how that horse touches others during a frightening time. I suggest you do with this movie what I advise all my acting students do with art in general: Don't judge too quickly. Let it wash over you in the dark. Allow it to manipulate you. That's why we go to the movies.

Thursday, February 9, 2012

Class is Only the Beginning

Actually, if learning to act is just about adhering to someone's else quotes about it, then John Gielgud may have better advice for young actors, "Before you can do something you must first be something."

So many actors just starting out seem to believe that taking a class and auditioning is all it takes to call yourself an actor. (I say this having had the same misplaced attitude, lo these many years ago.) But it's what you do between classes and before auditions that make you a true actor. Does a musician just pick up an instrument a play a concert? No. There are hours upon hours of rehearsal, playing scales, practicing a particular piece of music. There's is the care and tuning of the instrument. Oh, yeah, and the rehearsal. I'm wondering if Yo-Yo Ma or B.B. King only played their instruments when a teacher was around? And when they were done playing, I wonder if they just tossed their instrument on the sofa until they needed it again. Doubtful.

Taking an class does not make you an actor any more than owning a fiddle makes you a concert violinist. But acting class is a place where you go to learn to play your instrument. Where you learn to tune it and care for it. It's a place where you pick up tips on how to get the right sound out of it; when to play fast or slow; when to play loud or soft. When to contort the strings violently to your will or when to gently stroke them. An acting class is a place where you learn how to play with other musicians in concert. How to form chords. When to let someone else take the lead and when to pull back and settle into the rhythm. It's also a place where you get to try out different styles of music in the form of scene work or monologues. Maybe for a very few, a little improvisation if it makes sense for your particular instrument or style of music.

AFTER class is over, go act. Find a play. Audition. Do something. Do another scene in class, hell, another class for all I care. Learn a new monologue on your own, memorize a whole play, whatever. There is no excuse not to pursue roles wherever you can find them. Sure, I know, you are holding out for the big pay day that a series or blockbuster film role will give you. But don't just wait around for it to magically happen. Just like Yo-Yo and B.B., you gotta play the bars and piddly little stages. You have to work for a couple of beers or, maybe if you're lucky, a couple bucks to buy some Ramen. That's just the way it is. Those are the rules. No matter what city you are in those are the rules. Keep your trumpet polished. (Uhm, okay, maybe that one means the opposite of what I meant for it to mean.)

When actors comes to my class, there is an unspoken contract. They are agreeing that they are going to be...an actor. All in. That means they are going to do more than just show up to class. It means they are going to take everything they learned in class and put it into practice somewhere else. The class isn't the end, it's the means to an end. One of them, at least. It means they are going to learn their lines and maybe bump into the furniture until their shins bleed. Finally, it means they are going to stop listening to those that think because they are the class clown or funny at parties, that they would make a great actor.

Let's face it, not everyone is cut out to be an actor. It takes work. Talent helps, but work separates the wheat from the chaff. (And no, I am not going to switch from music metaphors to agricultural ones. That would be too much even for me.)

Many years ago, Les Paul gave me an autographed guitar. Now, I'm not a guitar player, but I have a beautiful, un-played guitar signed by the man himself. I cherish it. But, If I took that guitar and charged people to hear me play, it would cheat them and dishonor Lester.

Before you go "do" acting -- "be" an actor. All in. Tune your instrument, maintain it religiously and play it whenever you get the chance. Oh, yeah, and learn your f**king lines.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Glorious Eccentricity

Right after acting school, I got a job as a waiter. Of course. But, after a couple of years of slinging tostada salads and #2 combos (one taco, one cheese enchilada, rice and beans) I got tired of my clothes smelling like lard and my fingers like parsley. That and the fact that memorizing celebrity cocktail preferences was never my bucket of ice. (Dean Jagger did like his Ramos Fizz, though.) One day, after the perfect service of a very complicated special order, Dustin Hoffman stiffed me. Well, his wife stiffed me. Ratso Rizzo sat there and let her. That was the last burrito.

Lucky for me, I got a job at the Mayfair Music Hall in Santa Monica. The Mayfair was beautiful old girl. A delightfully garish old relic straight out of the Hollywood history books. Smelled like mold and old books. It sat boarded up for years after the Northridge quake and was finally razed a year or so ago. Very sad, indeed. My wife and I went by one day to try a swipe a brick out of the ruins but couldn't get over the fence.

The new owners at the time were trying to make a go of turning it into a legit house. Alvin Epstein directed Bud Cort in "Endgame," Phillip King performed his one-man "A Dicken's Christmas," the brilliant Jasper Carrott and the legendary Charles Piece both came in for special one-offs to pay homage to the music hall roots of the place. (If you don't know who either of these performers are, Google them. You're missing out.) And then..."Sherlock's Last Case." It was directed by the play's author, the irascible and eccentrically brilliant, or rather brilliantly eccentric, Charles Marowitz.

Charles is a critic, a director and a playwright. He is known for his outrageously, sub-text oriented, collage adaptations of Shakespeare, for his collaborations with Peter Brook, and for being one of the founders, along with Thelma Holt, of the Open Space Theatre. "Sherlock's Last Case" is easily his most successful and most well-known work. Beginning with it's world premiere at the Los Angeles Actor's Theatre in 1984 to it's re-staging in 1985 at the Mayfair and through to it's Broadway run with Frank Langella as the aquiline sleuth, the play has become a regional and community theatre stalwart. Not a brilliant play, but an entertaining couple of hours.The small cast and, basically, single set makes it possible for the most technically challenged regional groups. Doyle purists hate it, regular folk love it. Bonus points to Charles for the highly entertaining "A Background Note" in the acting script.

Regarding his approach to Shakespeare, he was once quoted as saying, "Imagine that Shakespeare's play [Hamlet in the case] is a precious old vase, and someone comes along and smashes that vase into a thousand pieces. If one were to take those pieces and put them back together, the arrangement would be new. That is, I suppose, what this (production) is. Shakespeare provides the vase and I provide the glue." The problem with this construction method is that you take a perfectly good vase, smash it to bits and hope it holds water, or even flowers, when you are done putting it back together. Of course, with Marowitz, what he ends up with isn't Shakespeare. It's Marowitz. No matter what you think of the process or the product, he has created something new and done it with flair, panache, daring and confidence.

Love him or hate him, Marowitz is one of those guys that makes the Theatre entertaining. (emphasis intentional). For a couple of years, he wrote an immensely enjoyable blog entitled, An Actor Prepares. I haven't seen a new post for over a year now, but I hope he returns to it if he is able. He is witty, sarcastic, stern, intelligent and more than a little opinionated. Anyone remotely interested in the stage should read a little Marowitz every once in awhile. He will help remind you why you were drawn to it in the first place. Of course, if you are like me, you may also think that he's absolutely full out it occasionally, but so what? Aren't we all?. One of my favorite entries is one of the earliest: APHORISMS FOR THE YOUNG (AND NOT SO YOUNG) ACTOR. (I'll be stealing some of these for my Facebook updates.)

Now, Charles Marowitz wouldn't remember me from a ham sandwich (figurative and literally), but I have remembered him, followed his work and enjoyed his writings lo these many years later. The world needs more Charles Marowitz's. Those glorious eccentrics who actually have something to say and say it in their own unique way. If we don't get it, that's our problem.

Lucky for me, I got a job at the Mayfair Music Hall in Santa Monica. The Mayfair was beautiful old girl. A delightfully garish old relic straight out of the Hollywood history books. Smelled like mold and old books. It sat boarded up for years after the Northridge quake and was finally razed a year or so ago. Very sad, indeed. My wife and I went by one day to try a swipe a brick out of the ruins but couldn't get over the fence.

The new owners at the time were trying to make a go of turning it into a legit house. Alvin Epstein directed Bud Cort in "Endgame," Phillip King performed his one-man "A Dicken's Christmas," the brilliant Jasper Carrott and the legendary Charles Piece both came in for special one-offs to pay homage to the music hall roots of the place. (If you don't know who either of these performers are, Google them. You're missing out.) And then..."Sherlock's Last Case." It was directed by the play's author, the irascible and eccentrically brilliant, or rather brilliantly eccentric, Charles Marowitz.

Charles is a critic, a director and a playwright. He is known for his outrageously, sub-text oriented, collage adaptations of Shakespeare, for his collaborations with Peter Brook, and for being one of the founders, along with Thelma Holt, of the Open Space Theatre. "Sherlock's Last Case" is easily his most successful and most well-known work. Beginning with it's world premiere at the Los Angeles Actor's Theatre in 1984 to it's re-staging in 1985 at the Mayfair and through to it's Broadway run with Frank Langella as the aquiline sleuth, the play has become a regional and community theatre stalwart. Not a brilliant play, but an entertaining couple of hours.The small cast and, basically, single set makes it possible for the most technically challenged regional groups. Doyle purists hate it, regular folk love it. Bonus points to Charles for the highly entertaining "A Background Note" in the acting script.

Regarding his approach to Shakespeare, he was once quoted as saying, "Imagine that Shakespeare's play [Hamlet in the case] is a precious old vase, and someone comes along and smashes that vase into a thousand pieces. If one were to take those pieces and put them back together, the arrangement would be new. That is, I suppose, what this (production) is. Shakespeare provides the vase and I provide the glue." The problem with this construction method is that you take a perfectly good vase, smash it to bits and hope it holds water, or even flowers, when you are done putting it back together. Of course, with Marowitz, what he ends up with isn't Shakespeare. It's Marowitz. No matter what you think of the process or the product, he has created something new and done it with flair, panache, daring and confidence.

Love him or hate him, Marowitz is one of those guys that makes the Theatre entertaining. (emphasis intentional). For a couple of years, he wrote an immensely enjoyable blog entitled, An Actor Prepares. I haven't seen a new post for over a year now, but I hope he returns to it if he is able. He is witty, sarcastic, stern, intelligent and more than a little opinionated. Anyone remotely interested in the stage should read a little Marowitz every once in awhile. He will help remind you why you were drawn to it in the first place. Of course, if you are like me, you may also think that he's absolutely full out it occasionally, but so what? Aren't we all?. One of my favorite entries is one of the earliest: APHORISMS FOR THE YOUNG (AND NOT SO YOUNG) ACTOR. (I'll be stealing some of these for my Facebook updates.)

Now, Charles Marowitz wouldn't remember me from a ham sandwich (figurative and literally), but I have remembered him, followed his work and enjoyed his writings lo these many years later. The world needs more Charles Marowitz's. Those glorious eccentrics who actually have something to say and say it in their own unique way. If we don't get it, that's our problem.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Non-Traditional Casting: My Crisis of Conscience

I've talked about this subject before. However, a recent article in the LA Stage Times got me going again. Here's the elevator speech if you don't want to click and read the whole thing: Joe Stern (whose work I respect very much) of the Matrix Theatre Company (a stalwart of the LA theatre scene for 40 years) is mounting a multi-racial production of Arthur Miller's All My Sons (in my opinion, one of the finest American dramas ever written).

Those who know me well, know I have long been a proponent of color-blind casting whenever possible. There are too many fine actors of color not to allow audiences the privilege of seeing them ply their craft. However, I'm am truly struggling with the application of this concept to historical works. Or rather, works that rely on a very particular set of historical or cultural circumstances that by their very essence require a particular outlook towards casting.The desire to include racial diversity in our casting decisions should never be forced or seen as a marketing strategy. It should be organic and true. It should make sense given the time, place and circumstances of the play.

Now, in the case of many Shakespearean plays, we can adapt them, bend them, twist them into a concept that supports a multicultural cast. Easy-peezy-lemon-squeezy with The Tempest, Much Ado, Twelfth Night, or Midsummer Night's Dream. But even with the Bard, there are some plays that, if done straight, just do not work unless the director conceptualizes them away from their original history and deals with that shift in a creative and justifiable way. Julius Caesar, all the Henrys, Richard III, and Coriolanus for example are real people from a particular place in history.

Now Joe Stern is no dummy. He knows what he's doing and even in the article, he specifically states the challenges he faced in casting this play the way he did. The play was written in 1947 and takes place in 1946 with World War II still fresh in everyone's mind. It is set in the Midwest, where a racially mixed neighborhood was, well, let's just say, highly unlikely. Granted, the issues examined in this play are universal and large. Which then begs the question, what does the casting do to advance the meaning of the play?

Now, I'm pretty confident, there will never be a mixed race cast of August Wilson's The Piano Lesson. Nor should there be. David Henry Hwang's first play, FOB, must be cast is a particular way. It is too specific. How are those plays any different that the Miller play? Does age make it susceptible? Are the concepts presented by the drama so large and universal that casting really doesn't matter? Just thinking out loud, I guess.

You see, for me (I think, any way...at least right this second) we have become so concerned about non-traditional casting that we fail to advance the real issue. Playwrights must write for a multicultural society. Producers must nurture playwrights of all nationalities. Film, TV and the theatre must continue to fight racial stereotypes not just by selective casting, but by play selection. The issue is really about creating for a multicultural society in the first place, instead of trying to shoe-horn multicultural casts into existing works of the theatre.

Then again, I guess what I would really like is that it wasn't an issue at all. The best actors would get the part regardless of race, color, creed, or sexual orientation. I wouldn't have to think then.

Oh yeah, go see All My Sons at the Matrix: Here's the website for tickets. Regardless of what I may think I believe at this moment in time -- this is a great play, with an excellent cast, at a theatre known for exceptional productions. I'm going. Maybe it'll help me sort things out.

Those who know me well, know I have long been a proponent of color-blind casting whenever possible. There are too many fine actors of color not to allow audiences the privilege of seeing them ply their craft. However, I'm am truly struggling with the application of this concept to historical works. Or rather, works that rely on a very particular set of historical or cultural circumstances that by their very essence require a particular outlook towards casting.The desire to include racial diversity in our casting decisions should never be forced or seen as a marketing strategy. It should be organic and true. It should make sense given the time, place and circumstances of the play.

Now, in the case of many Shakespearean plays, we can adapt them, bend them, twist them into a concept that supports a multicultural cast. Easy-peezy-lemon-squeezy with The Tempest, Much Ado, Twelfth Night, or Midsummer Night's Dream. But even with the Bard, there are some plays that, if done straight, just do not work unless the director conceptualizes them away from their original history and deals with that shift in a creative and justifiable way. Julius Caesar, all the Henrys, Richard III, and Coriolanus for example are real people from a particular place in history.

Now Joe Stern is no dummy. He knows what he's doing and even in the article, he specifically states the challenges he faced in casting this play the way he did. The play was written in 1947 and takes place in 1946 with World War II still fresh in everyone's mind. It is set in the Midwest, where a racially mixed neighborhood was, well, let's just say, highly unlikely. Granted, the issues examined in this play are universal and large. Which then begs the question, what does the casting do to advance the meaning of the play?

Now, I'm pretty confident, there will never be a mixed race cast of August Wilson's The Piano Lesson. Nor should there be. David Henry Hwang's first play, FOB, must be cast is a particular way. It is too specific. How are those plays any different that the Miller play? Does age make it susceptible? Are the concepts presented by the drama so large and universal that casting really doesn't matter? Just thinking out loud, I guess.

You see, for me (I think, any way...at least right this second) we have become so concerned about non-traditional casting that we fail to advance the real issue. Playwrights must write for a multicultural society. Producers must nurture playwrights of all nationalities. Film, TV and the theatre must continue to fight racial stereotypes not just by selective casting, but by play selection. The issue is really about creating for a multicultural society in the first place, instead of trying to shoe-horn multicultural casts into existing works of the theatre.

Then again, I guess what I would really like is that it wasn't an issue at all. The best actors would get the part regardless of race, color, creed, or sexual orientation. I wouldn't have to think then.

Oh yeah, go see All My Sons at the Matrix: Here's the website for tickets. Regardless of what I may think I believe at this moment in time -- this is a great play, with an excellent cast, at a theatre known for exceptional productions. I'm going. Maybe it'll help me sort things out.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Supporting Casts Make the Movie

...or TV show or play. I watched the season premier of the US version of Prime Suspect. Now before you say anything, no it is NOT the same as the original UK version with the fabulous (and still hot) Helen Mirren. Not supposed to be. Apples and oranges. Same title, sorta the same premise and the lead character has the same first name. Whatever. It's a good show. I like it. Maria Bello is strong in a part not typical for American TV. BUT (notice the capital letters for emphasis?), what I truly love about the show is the supporting cast. Great character actors you've seen a million times yet probably don't know their names. Brian O'Byrne, Kirk Acevedo, Peter Gerety -- all actors you have seen hundreds of times. These are the people Liz and I always say, "Oh, I love that guy! He was in that other thing. What's his name?"

The idea that a great supporting cast can save an otherwise forgettable movie is not a new one. My in-laws used to say that when they were young they would go see any movie that had Thomas Mitchell or Barry Fitzgerald in it. For me it's Ward Bond. And Thomas Mitchell. And Ruth Hussey. Oh, and Edward Arnold, H.B. Warner, Mary Astor and a dozen other character actors that will always turn in an amazing performance no matter what. If fact, I'll go so far as to say that John Wayne was so incredibly famous because, in every movie he ever made, he was surrounded by great supporting players. They made him appear better than he really was.

Classic movies (you know, like you see on TCM) are great examples of putting together great actors around certain movie stars to make a movie work. Oh sure, Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell are perfect in His Girl Friday, but imagine what that movie would have been like WITHOUT Gene Lockhart, Abner Biberman or Clarence Kolb. The same holds true today. If a movie has a star I don't necessarily care for or don't know all that much about, I will take a risk on it based on the people around him. I am not a big Leonardo Dicaprio fan. I, generally, just never believe his performance. However, I went to see Inception when it was out. The supporting cast made that movie for me and, as a result, I actually enjoyed Leo.

Not all character actors were or are movie stars, or even famous for that matter. The cast in Prime Suspect is a perfect example. And quite frankly, not all movie stars should be famous. They should be characters actors, second fiddles that make up a great cast. Ben Affleck (for my money) can't carry a movie on his own -- as the star. But, he is a very capable supporting actor. Dare I say, excellent. Shakespeare in Love and State of Play are examples of Ben's ability to create memorable performances -- just not leading ones.

This idea is true on stage and on TV, too. Broadway has made a living lately by injecting "big name" stars into limited runs of things. Of course, the regular cast of Chicago does all the heavy lifting while songwriter and former American Idol judge Kara DioGuardi dances around as Roxie Hart. Somehow it's all forgiven when the the supporting players make her look like she belongs there.

So, before you blow off seeing any movie or TV show or play, look up the names NOT on the poster. If it's a classic film and has Ward Bond or Thomas Mitchell in it, for sure watch it. It'll be great! Guaranteed.

The idea that a great supporting cast can save an otherwise forgettable movie is not a new one. My in-laws used to say that when they were young they would go see any movie that had Thomas Mitchell or Barry Fitzgerald in it. For me it's Ward Bond. And Thomas Mitchell. And Ruth Hussey. Oh, and Edward Arnold, H.B. Warner, Mary Astor and a dozen other character actors that will always turn in an amazing performance no matter what. If fact, I'll go so far as to say that John Wayne was so incredibly famous because, in every movie he ever made, he was surrounded by great supporting players. They made him appear better than he really was.

Classic movies (you know, like you see on TCM) are great examples of putting together great actors around certain movie stars to make a movie work. Oh sure, Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell are perfect in His Girl Friday, but imagine what that movie would have been like WITHOUT Gene Lockhart, Abner Biberman or Clarence Kolb. The same holds true today. If a movie has a star I don't necessarily care for or don't know all that much about, I will take a risk on it based on the people around him. I am not a big Leonardo Dicaprio fan. I, generally, just never believe his performance. However, I went to see Inception when it was out. The supporting cast made that movie for me and, as a result, I actually enjoyed Leo.

Not all character actors were or are movie stars, or even famous for that matter. The cast in Prime Suspect is a perfect example. And quite frankly, not all movie stars should be famous. They should be characters actors, second fiddles that make up a great cast. Ben Affleck (for my money) can't carry a movie on his own -- as the star. But, he is a very capable supporting actor. Dare I say, excellent. Shakespeare in Love and State of Play are examples of Ben's ability to create memorable performances -- just not leading ones.

This idea is true on stage and on TV, too. Broadway has made a living lately by injecting "big name" stars into limited runs of things. Of course, the regular cast of Chicago does all the heavy lifting while songwriter and former American Idol judge Kara DioGuardi dances around as Roxie Hart. Somehow it's all forgiven when the the supporting players make her look like she belongs there.

So, before you blow off seeing any movie or TV show or play, look up the names NOT on the poster. If it's a classic film and has Ward Bond or Thomas Mitchell in it, for sure watch it. It'll be great! Guaranteed.

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Why I Hate the Business of Acting or, "Why, Grandmother, what big brass balls you have."

My wife and I come from the

theatre. We met doing summer Shakespeare some 20mumble years ago. We love

acting, actors, the theatre, film and, yes, even television. We try to see as

much as we can. We stay up on who's doing what, articles, books, new plays. So,

naturally, we find ourselves deconstructing things, re-imagining productions,

reviewing the performances we see, the directors' choices, and so on. If you have stumbled on

this site, no doubt you do the same.

One thing we continue to talk

(read: lament) about is the "business" of acting. From workshops to

head-shots, from trade magazines to web site design. There are literally

hundreds, if not thousands, of people luring you to spend money with them with

veiled and sometimes not-so-veiled promises of "reaching your goals," booking more jobs" or

"learning the secrets" to the business of acting. Cold reading

workshops abound. Camera technique classes are ubiquitous. Photographers

specializing in head shots, in Los Angeles anyway, are as common as Starbucks.

It seems more and more that the

business is overtaking the craft. Judging from the increasing number of times

we see transitional figures in popular culture being provided undeserved acting

opportunities, it appears there is no end in sight. For example, Justin Bieber

got a two episode arc in CSI; Eminem

did a quasi-autobiographical turn in 8

Mile. Most recently, Justin Timberlake has been working none stop on the

big screen. Okay, I get it. It is a business after all. Networks and production

companies have a right to make money and try to attract the largest number of

people to their product as possible. No problem. And, yes, I know this isn't a new thing. It just seems more prevalent than ever before.

But recently, I have feared for what

this says to young actors just starting out. It says you don't need to

train to become an actor. It says fame is more important that art. I says

personality and appearance is more important that humanity and understanding.

The business of acting reinforces this.

Recently, my wife told me of

professor at her university who has published what one articled called the

"Quintessential Book on Acting." Wow. Really? One book? In this

particular interview the author (also an actor) is quoted, “I did all the work for the actor and

distilled everything they need to know into a readable and usable form. This is

the only book the actor needs.” The article goes on to say that "the author intentionally designed the book

to be short and physically small enough to go into an actor’s back pocket. This

way the actor can quickly refer to it as needed."

Again, wow. Where was this book when

I was just starting out? You mean that my classmates and fellow actors didn’t

need to read Shakespeare or Mamet? We didn’t need to know about Kristin

Linklater or Cecily Berry? We wasted all that time studying world history,

literature, languages, race relations, bigotry, jealousy, greed, power, current affairs, family dynamics, ego, stage

directions, costumes, beats, inflection, sense memory, Stanislavski, Meisner,

Strasberg, Boleslavky, Chekov, Don Richardson, Peter Hall, Neil Simon,

Tennessee Williams?

Apparently, if you listen to the business, actors no longer have

to experience life. Apparently, to study the human condition is unnecessary. Technique

has given way to pure celebrity. Well, and a quick read that tells you everything you need to know.

I have always and honestly

believed that the best actors in America are not making movies or starring on

TV. They are in regional theatres spread across the country. They are working

tirelessly in 99-Seat Plan (what we used

to call Equity Waiver) houses in Los Angeles and in tiny Off-Off-Broadway

showcase venues in New York City. They have transitioned into other professions

in order to make a living. They have left their once passionate relationship

with the craft of acting to become writers in Washington, massage therapists in

Santa Monica, counselors in San Jose, teachers in Arizona, university administrators

in L.A. and food servers in the Big Apple. Unfortunately, with the business of

acting entirely cut off from the nation's best training centers, there is no

balance. No feeder system that gets the best actors into the system of

Hollywood or the factory of Broadway.

Of course, if you buy this one

book….

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)